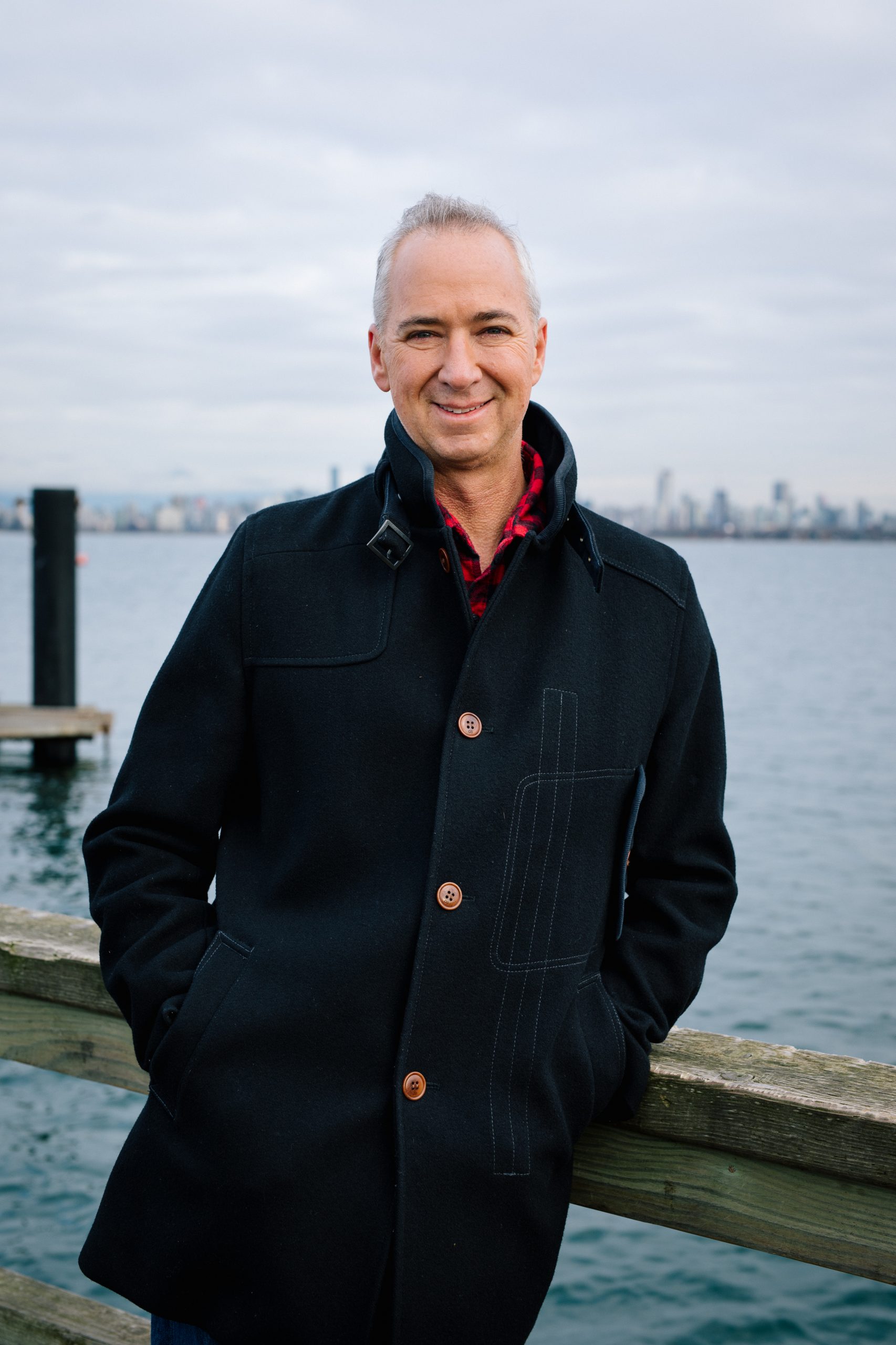

In 2019, writer, speaker, activist, and comedian Baratunde Rafiq Thurston delivered a TED talk that MSNBC’s Brian Williams deemed “one of the greatest of all time.” It has since garnered more than 5.3 million views.

In it, he discussed the “weaponization of White supremacy, the deadly consequences of policing, and the power of language to write a better narrative for us all to inhabit.”

This New York Times bestselling author of How To Be Black is known for holding space for hard and complex conversations. In addition to his TED talk, he is an Emmy-nominated host who has worked with The Onion, produced for The Daily Show, and been an advisor to the Obama White House administration.

He also carries his poignant message through his podcast, How To Citizen with Baratunde—one of Apple’s “favorite podcasts of 2020.” At the 2021 iHeartRadio Podcast Awards, the show earned him the Social Impact Award for his discussions of themes like race, culture, and politics.

Baratunde’s drive to explain where our nation is, and where we can take it, is a direct reflection of his ancestry.

His grandmother was the first Black employee at the U.S. Supreme Court building, and his mother, “the most resourceful and intelligent person” Baratunde has ever known, was a self-taught computer programmer who took over radio stations in the name of the Black Liberation struggle.

Suffice it to say, he grew up unabashedly questioning authority and forging his own path.

He went on to earn a philosophy degree from Harvard, and then co-founded the new media startup, Puck.

Without question, Baratunde has a propensity for shaping the world in which we live, and he doesn’t hold back:

“I try not to pull back on things that I believe in because I worry someone might disagree with me. I launch so many opinions and thoughts into the world, and not everyone agrees with them all. I’m okay with criticism—even the criticism that I really don’t think has merit—because I have launched criticism that has no merit.

“In most cases, there’s some element of truth in all criticism. For example, I made a stupid joke in my newsletter about how Texas was making it harder for women to get an abortion while Mexico was making it easier. And I was like, ‘Even the narcos state of Mexico has given more rights to women than the allegedly free Republic of Texas.’ I was very proud of myself for making the comparison. The state [Texas] that thinks it’s so much better and freer than others doesn’t trust its own women to make a free choice for themselves. And Mexico, with all of its perceived ‘problems,’ is outdoing us in the liberty department.

“I kind of threw Mexico under the bus when I called it a ‘narco’ state; it wasn’t kind or accurate. Somebody called me out on it, and tried to fire up a change.org petition on Twitter to make sure I can never email again. I heard the charge, and it made me think. I acknowledged what the person was saying and apologized.

“Now, that’s not to say that I won’t continue to rag on Texas and their retrograde, extremist, religious-based policies about what their fellow Texans can choose for their medical and healthcare. But I will think more about how I’m saying what I need to say now.”

This perspective on criticism may go hand-in-hand with Baratunde’s understanding of a key concept he has come to embrace with age: that he has a very limited set of data from which to base his thoughts, perspectives, ideas, and beliefs about the world.

“Growing up where I did, I listened to local radio stations, watched local news, and read local papers,” he said. “All the input entering my mind was based on a very limited scope of the total amount of data available. Whereas someone growing up in a different place with different people, feeds, and sources would receive very different input.

“So, I clearly recognize that it is entirely possible that everything I believe to be true actually isn’t.

“Based on this perspective, we could be wrong about so many things. Being open to being wrong is a special power… one that I am certainly not always willing to embrace. But in the moments when I do, and I can find that gratitude, I feel good. I am open to what it might unlock for me. I wish this power for everyone, sincerely.

“We’re a very diversified country. We have a lot of languages, cultures, and religions. We’re trying to live together with a ton of differences, and that’s hard. So having a bit of Zen in this respect can really help, in terms of the citizen work.”

Part of that citizen work is helping define the future of media as “a rare leader who sits at the intersection of race, technology, and democracy and seamlessly integrates past, present, and future,” as he has come to be known.

One of the ways he accomplishes that mission is by turning the word “citizen” into a verb. In How To Citizen, now in its fourth season, he reminds people that they don’t just have to “scream at the news or vote for people.”

Rather, he says, “The power of the people is real. My podcast is about reminding people of the different ways we can all actually leverage the power of the people. That’s what democracy is supposed to be. We explore that and reiterate to listeners that there’s a whole bunch of different ways we can collectively, and individually, shape our society.”

Baratunde started podcasting in the early 2000s. At the time, he lived in Boston, and he hosted a low-power FM radio show on a small station called “Alten Brighton free radio.” It had only a two-mile broadcast radius, which meant he couldn’t even listen to his own show in his apartment. So, he started recording the episodes and converting them to MP3s that he could then post on his website.

“I was basically begging on air. I was like, ‘If you can hear my voice, call me! Send me an email,’” he laughed.

What began as “a revenue-neutral creative experiment” ultimately launched his love of audio:

“I have a very real appreciation of what this medium can do. It’s intimate, and it’s connected. It’s a method of creating your own educational experience. It’s also an art.”

Having fallen in love with podcasting as a listener and as a host, Baratunde knew it was the perfect medium for him to convey his message when he felt the need to restore his faith in America following the killing of George Floyd, among others, and all that came with COVID-19 in the summer of 2020.

“There was just this tightness… this hurt,” he said. “It really challenged my faith in country. In short, democracy wasn’t being done.”

Thus, How To Citizen was born.

Seeking to create an educational experience for others, he was determined to address critical issues that no one else seemed to be taking on in the medium.

“There are a lot of technical, top-down news headlines—the ease or challenge of voting, the lack of responsiveness of elected officials to those who elected them. But other things, like wealth inequality, which is currently at Depression-era levels that are not good for the whole, weren’t being addressed.

“I had also reached my threshold of being told that ‘Everything is bad, and there’s nothing you can do about it.’ That’s generally what the news tells us. ‘Everything’s on fire, and you’re going to burn. And there are no fire departments.’ There might be one fire extinguisher in a single human interest story, but that’s about it. And I didn’t believe that. In fact, I knew the opposite was true.”

Baratunde uses How To Citizen as a vehicle for bringing issues like the aforementioned wealth inequality front and center.

“In this country, we punish the poor. We’ve made poverty this sort of moral failure, attributing it to not working hard enough. Then, you have to unlock these levels of living—dental, vision, primary care. It’s gotten to the point where we’re proud if we can go a certain amount of time without paying for insurance.

“Why do we live in a society where that’s even an option? We could definitely cover everybody, but we don’t. And so, we let a lot of people fall through the cracks, and then, we blame them for doing so. It’s like, if you are so unfortunate in this capitalistic society as to be among the very poor, we’re going to make everything harder for you. It’s hard to get a job. It’s hard to get a house. And then, we punish people for seeking assistance.

“So how do we break that cycle? Well, that’s what we covered in the second season of How To Citizen. There are actually 12 episodes answering this question.”

Baratunde is passionate about tackling such issues on his show, which is based on the following four pillars:

- Show up and participate. Baratunde points to Ukraine as an extreme-yet-simple example. “There are people who are showing up and blocking Russian tanks,” he said. “That’s an extreme way to show up. We saw it in Tiananmen Square, too, and in the civil rights movement. Sit-ins, marches… it’s about being present. It means something, when someone shows up, even if doing so won’t fix the issue singlehandedly. And we can show up in multiple ways. Your presence has power.”

- Invest in relationships with yourself, with others, and with the world around you. “We can’t do it alone,” Baratunde explained. “It’s about valuing interdependence and recognizing our connection with other forms of life that we’re dependent on—what we eat, or those that breathe for us, in the case of trees. There’s also the relationship with yourself, which we often skip in this kind of civics conversation generally about delegates and all that kind of stuff. What do we want? How do we want to live? How do we want to experience this life? How do we want to feel in this country? What are we afraid of? We really have to be in touch with ourselves. And we have to be in community with others for this to work, because we can’t build a bridge by ourselves.”

- Understand your power. “Here,” Baratunde said, “we unpack the word ‘democracy.’ It’s Greek, essentially meaning ‘people power.’ If we’re truly embracing that form of self-government and ability to control our destiny, we have to understand people and relationships. We have to understand power. When we say, ‘They’ve got all the power,’ do they actually? What is the power? What forms of power are we talking about? And when we become fluent in that understanding and recognize all the different ways that we can generate and use power, it makes us ALL more powerful.

“I’ve internalized a lot of lessons around there being people with power and people without power. The powerful people are always ‘over there’ somewhere. And then the rest of us are over here without power. But if we just got together and made a joint decision to commit our resources together, all of a sudden, that’s power. And those resources don’t have to be money. They don’t have to be tanks. They can be our bodies. They can be our attention.”

- Value the collective valuing. “For as selfish as we are encouraged to be as individual economic units within our economic system, we benefit individually when we benefit together. So if, as one of our guests, Valerie Core, says, we can see a stranger as a part of ourselves… if we can see one another as family a little bit more instead of having the zero sum mentality (someone else winning means I have to lose) and let go of the fear that someone is trying to take something from us… we all benefit.”

Baratunde and his guests have one major goal in common: improving society for the many.

His hope is that listeners will be moved to act for the greater good of us all.

“But if they were, we wouldn’t have had to write them down.”

On July 5, PBS is releasing his new show, America Outdoors with Baratunde Thurston. In it, he travels the country to explore “How beautiful we are and can be.”

A perfectly fitting description of not just the show, but the essence of Baratunde’s work.

July 2022 Issue